|

Whoever claimed that killers had sweet dreams, never met Connie. She woke in her grandparents’ living room, sprawled on wet carpet. The bogeyman that chased her in a nightmare wasn’t as terrifying as her heart-thumping reality. She’d helped Grandma kill Grandpa. Connie had drifted to dreamland for only sixteen minutes. Her hands stung, rubbed raw from scrubbing bloodstains. She’d watched enough CSI to know she should’ve used bleach, but it would’ve faded the chocolate brown shag. Premeditation and conspiracy made the murder first degree, but cops couldn’t arrest Grandma for swinging the bat. Mortals couldn’t confine a ghost. Trembling, Connie swaddled the stiff in towels and a tarp, wrapped the leaking cocoon in duct tape. Weeping, she dragged Grandpa’s corpse to the garage and stuffed him into the Buick Regal’s trunk. She climbed into the driver’s seat and cranked the key. The engine rumbled reassuringly. “You think God believes in an eye for an eye?” Connie asked. “Don’t worry dear,” Grandma replied. 4:15 AM, too early for rush hour traffic. Connie squeezed the steering wheel in a white-knuckle grip, drove under the speed limit, west on Division Street, south on Lawndale Avenue, until they reached Humboldt Park. “You sure you want to leave him here?” Connie asked. “It’s where he left me,” Grandma replied. Robins and wrens serenading the rising sun quit chirping when the ghost shoved the body into the lagoon. It bobbed before it sank. Invisible arms wrapped Connie in an embrace. Grandma exhaled ectoplasm that smelled like spring rain.  Alicia Hilton is an author, editor, arbitrator, professor, and former FBI Special Agent. Her poems have been nominated for the Rhysling Award and the Dwarf Stars Award. Her work has appeared in Back 2 OmniPark, Creepy Podcast, Dreams & Nightmares, Eastern Iowa Review, Egaeus Press, Litro, Modern Haiku, Mslexia, Neon, NonBinary Review, Not One of Us, Space and Time, Stoneboat Literary Journal, Vastarien, World Haiku Review, Year’s Best Hardcore Horror Volumes 4, 5 & 6, and elsewhere. Her website is https://aliciahilton.com. Follow her on Twitter @aliciahilton01 and Bluesky @aliciahilton.bsky.social.

0 Comments

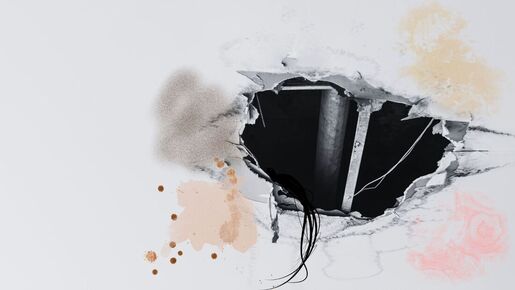

The ceiling sagged and dripped. Brown liquid fell onto cream carpets and filled the spare bedroom with a rancid air that alerted Moira to the leak before she saw the damage. "Probably a burst pipe. We'll have to shut the water off." Maintenance told her, arriving just in time to watch the ceiling pop. Within an hour, tape cordoned off the room. Various people came in and out of her apartment, wading through ankle-high murky water, shining flashlights into the fetid abyss above. Faces obscured with respirators carried ladders and vacuum pumps. The whirring of machinery forced her onto the balcony, watching through the window as people climbed into the ceiling. Only the sway of flashlights slicing through shadows indicated they existed up there. One by one, the beams disappeared. Darkness overtook the hole once more. Over quiet minutes, body language changed amongst the workers; furrowed brows and exaggerated motions spread through the crowd like a virus. Most were transfixed on the hole, shouting to those inside with the kind of timidity only borne of fear. Moira wandered inside, her head craning to see around the mob. A scream suffocated all communal curiosities and conversation. A choked, gurgled vocalization emanated from deep in the ceiling, like water poured into the throat of whoever made it. Chaos replied. Two workers rushed up the ladder, their silhouettes engulfed by the darkness, while the rest quickly made their leave. Moira remained on the far side of the tape, shouting to the workers inside her ceiling. Someone tumbled from the hole, crashing into the ladder's apex, bending across its metal before falling into the muck. Moira rushed into the room, checking on the man who convulsed in the murky water. As she bent to stabilize him, his mouth opened. Darkness extended forth from the back of his throat. Thick clumps of hair wound around his tongue and over his lips. Moira backed up in time to see black wisps extend down from the ceiling. Matted hair spread across her ceiling and down the walls like a spider's legs clinging to a corner. As she felt the first strands wrap around her wrists, she saw the twisted visages descend from the hole, writhing and choking, cocooned in the hair, and the cluster of sallow eyes at its core.  Steve Neal is a neurodivergent, English-born writer currently surviving the summers of Florida with his supportive wife and less supportive cats. As a lifelong horror fanatic, he enjoys poking at the unknown and seeing what comes crawling out, as long as it isn't spiders. His debut novella TO LOVE A DYING WORLD releases in 2025 through Off Limits Press. Follow him on Twitter @SteveNealWrites. Darkness wraps around him, he wears it like a cape striding like a king down empty midnight streets, a crown of stars above his head and bodies at his feet. Greg Schwartz lives in Maryland with his wife and children. Some of his poems have appeared in Talebones, Space & Time, Horror Carousel, and Writers' Journal. He was fortunate to win a Dwarf Stars Award in 2015. In a pre-fatherhood life he was the staff cartoonist for SP Quill Magazine and a book reviewer for Whispers of Wickedness.

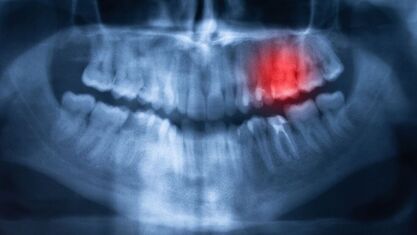

Twitter: https://twitter.com/freginold_JS Website: https://haiku-and-horror.blogspot.com/ The twins are up past their bedtime, the sounds of a bloody creature feature turned down low on the bubble-fronted basement television, so that their parents upstairs won’t hear them. They’re giddy with the rush of the forbidden, of trespassing, transgressing. It’s a glee that’s cut short just when it’s getting good, when the monster is about to be revealed, because the television cuts to black. But it’s timed wrong, in the middle of a scene, in the middle of a line of dialogue, so they keep their eyes on the screen, and see only a grainy close-up of a man sitting in front of a black and white chevron background. It is not an ad. Not any they’ve ever seen. And it’s not a man. Not any they’ve ever seen. His smile, his whole face is unmoving. Sunglasses shield his eyes, his hair a platinum plastic pompadour. “They… are coming… to get me,” he says from behind the mask. The boys know that they shouldn't see this, even more so that they shouldn’t have been watching the monster movie. Not in the sense that it came to them by mistake, but that they shouldn't. See. This. That it's against some rule of the world they don't understand yet. They look at one another, the silent question, should we? drifting between them. When neither of them voices an objection, they confirm their decision. The masked man disappears, and they keep watching the unspooling of seemingly-unrelated images. They cannot look away (waves crashing against an unfamiliar, broken shore), suddenly imagining some invisible force holds them steady. Peels their eyelids open. Points their faces at the screen. When they take into account what they see on the television (a close-up of a woman with a ball gag in her mouth, looking wide-eyed into the camera), this seems less farfetched. And when it's all over, and the television has returned to its normal late-night rerun of whatever monster movie they were watching that no longer seems important, they can't describe what they've seen. Not entirely. Nor can they properly describe how it made them feel. Only in snippets can they do either. It's like the images (a brown paper bag over the head of a barefoot lady in a floral dress, hands held out at her sides for balance despite her standing in the grass) are part of a dream (she steps forward carefully, tentatively, unaware of the coiled snake by her feet). Not theirs, but someone else's they accidentally stumbled into. The feelings, however, the reactions, are entirely their own. The boys look at one another. Neither one of them speaks, but they each know the other is sweating (just like the blindfolded man, sweating, running, the look of terror on his face, the camera moving ahead of him, looking over his shoulder, spying the dark, loping, out-of-focus shapes he’s fleeing). Under their armpits. On their foreheads. Rivulets running down their backs (a shot from behind of a toned woman in the dark, her muscular back laced with fresh, bloody wounds, something moving in the darkness ahead of her, something she looks ready to fight again). The boys do not yet have the vocabulary to explain what they’ve seen, how it’s made them feel other than wrong (a woman in a pencil skirt bending herself over a pommel horse, looking back over her shoulder at the camera as she spreads her legs). And yet there is no proof that any of this ever happened. Nothing except their memories (the woman in the dress holds the snake carefully, coiled around her bare forearm, extended, holding it out like it’s going to fly away and she’s going to guide it), their feelings.  T.T. Madden (they/them) has been writing horror, scifi, and fantasy ever since they tried climbing (and were unfairly pulled from) their mother's bookshelves to reach her Stephen King novels. So to get their fix they visited the library, and their local Blockbuster (which didn't check ID). They have two books releasing in 2024; The Cosmic Color, a transfem mech/kaiju novella with Neon Hemlock, and The Familialists, a queer social horror with Off Limits Press. They can currently be found in the deepest, darkest part of the woods, finishing a folk horror novella. But for a more normal method of contact, try @ttmaddenwrites on Twitter, Instagram, Bluesky, and TikTok. Every woman in my family has known she was going to die when one of her teeth fell out. It’s our curse. I don’t mean the baby teeth, that would be truly fucked up and I wouldn’t even be here right now if that were the case. At some point in every Murray woman’s life, one of her molars will fall out to signal that her time is near. My mother, Winnie, knew she was going to die when she was in the middle of the grocery store trying to decide between a roast chicken and ground beef when a sudden crack resonated through her head. She felt the loose piece of bone swimming through her mouth towards her lips and held her hand out to spit out and bear witness to Death’s calling card. My dad tells me she just shakily placed the tooth in her purse and picked up the roast chicken. After all, my family still has to eat, she said. She died one week later. I was ten. The length of time is never consistent, but it’s always within a month. My aunt Tess died in the bus terminal still clutching onto the foreboding ivory that had fallen just moments ago. My grandmother held out for almost two weeks before whatever malevolent force took her away. Some of my family tried to fight it. My cousin, Emma, avoided all solid foods so as not to disturb any of her teeth. She died at Thanksgiving dinner with only pureed carrots and peas on her plate. My great-aunt Dot thought that if she super glued her tooth back into her mouth then that would trick the God coming to take her away. She lived the longest. Twenty days after she glued her tooth back in she passed away during a routine teeth cleaning. Her husband, Greg, insists that the hygienist knocked the tooth out of place and that she should be sued. Of course, those outside the family don’t understand our plights and Greg lost the lawsuit. And my poor sister, Judy. She was only twelve. She came into my room one night, tears sliding down her face, but she wouldn’t tell me what was wrong. She just asked if she could sleep in my room that night. When I woke up the next morning, my arms were wrapped around a cold body, and my sister had been taken at some point in the night. I found the tooth under her pillow a few days later. That was the last straw for me. That some stupid force in this universe would choose my twelve-year-old sister rather than someone else to die. She was still a kid. From that day on, my soul rotted to the core, and I turned bitter. Dad understood, but he wanted me to move on. Can you believe that? Move on when there’s a fucking curse on our family and every fucking woman born with the Murray name dies once one of their teeth falls out! How am I supposed to move on? How is anyone supposed to move on? Dad most of all. He’s lost his wife, his youngest daughter, and he thinks he’s going to lose me at some point. Well, he’s wrong. I’m not going to let some laughable curse take me away from this world before I say so. And, yes, I hate the world that I live in. Everyone I’ve loved has been taken away from me too soon and without reason. You’d think I’d be happy to die and finally reunite with all of my lost family members. Feel the warm embrace of my mother that I haven’t felt in fifteen years; crush my sister into a bear hug and smell the strawberry scent of her hair; laugh at my aunt Tess’ dirty jokes and watch the food fly out of my great-aunt Dot’s mouth as she cries hysterically. I would be reunited with all the wonderful, disgusting things that have left a gaping hole in my heart once I was left with a gaping hole in my mouth. And as much as I want, need to see them, I can’t do that before my time—my true time. I stare in the mirror now and smile. I smile bigger and bigger until I’m satisfied. My cheeks hurt from the magnitude of my grin, and tears leak from my eyes. I did it. I did it. I got every last one. My mouth is now just some yawning black hole. The pearly whites that were there my whole life, including the one to determine my destiny, are now gone. Pulled out; the roots ripped away like the maternal roots of my family tree. Pulling them out hurt, obviously. I rubbed an Ibuprofen gel capsule on my gums to numb them, but that didn’t stop me from feeling the twisting and yanking of twenty-eight teeth. Not to mention those that didn’t come out easily, breaking into shards and causing me to go back in more than once with my pliers. My fleshy pink gums glitter back at me as I continue to smile at myself, the tears of relief flowing freely down my face. I can feel my mouth humming from the exposed nerve endings, and I know realistically I’ll have to go to a dentist to fix that, but I let myself bask in my triumph. No more seeds of doubt will bloom within my mind, and the seed of my death will no longer take root nor flourish nor finally wither away and fall like the leaves in autumn. Whatever miserly deity rules over my family will not reap what they sowed in this Murray woman.  Katie Cossette (she/her) is a Montreal writer pursuing her BA in Honours English Literature. Her work has been featured in DarkWinter Lit, Ghost City Review, Alien Buddha, Wireworm, and elsewhere. Katie is currently the co-founder/co-EIC of Crab Apple Literary and you can find her on Instagram (nerd.i.am) and Twitter (cossette_katie). Mother made me from ten drops of blood. From whom they were taken, I do not know. She lived in the isolation provided by the forest. Not from choice but from necessity. Mother was different, she would say. Her solitude kept her safe but in due course, this same solitary life in which she lived had left her feeling lonely. But my mother, being so clever and smart, knew she had the proper way to remedy her situation. Ten drops of blood, from beneath a new moon To a ginger root, taken two weeks too soon Then bathed in milk, and dried in hair Will make the one, both tall and fair She was a very patient woman, my mother. She had gone to great lengths to teach me right from wrong, all the while knowing it was difficult for me. Although Mother was strict in her teachings and sometimes cruel, I knew her love for me ran as deep as the well from which she drank. She showed me the way of her name which I was clumsy to perform. But Mother said this was not my failing as I, too, was different. In fact, I was made different and would have to take my dimensions and form into account. But Mother taught me nonetheless. She also kept me safe. Told me the laws I must abide by. I was never to travel to town, for they knew not of our ways or my existence. Mother said they fear what they do not know. They would fear me. They certainly feared Mother. This was why she grew lonely. In spite of everything, I grew. All the while I still could not slow the passing of time. I was unable to stop death. Not even my mother, so witty and smart could do that. Although she had tried. She passed through this plane like smoke through a chimney. Vanishing above to leave only a blackness to stain the walls. Leaving only me. And like my mother before me, I, too, have grown lonely this way. I, too, was alone. Although I am neither as clever nor smart as she, I did know the way to remedy this. However, I have no blood to give. The new moon had come, the ginger was pulled, and all had been prepared except for this one thing. These, ten things. Mother would have certainly scolded me had she been alive to know where I was going. Even in death, I presume she knew. Ten drops is all I needed. I like to imagine I was assembled from Mother’s blood. I like to believe a piece of her still lives on inside me. Perhaps the only thing living inside me. I ducked below the branches to loom closer. How would I pick the one? Blazing lights cut through the darkness and seemed to stretch on forever between the neat rows of tiny houses, of the kind that I had never seen. I picked the one nearest to the trees. The dwelling was too small for me to fit inside, but the man outside would do nicely. He was gray like Mother. He was alone like Mother. He was alone like me. This one would suit me well. I looked down at him with a gleaming smile, excited at the thought of a creation of my own. My creation. I was ready. Ten drops is all I need.  Matt Bliss is a construction worker turned speculative fiction writer from Las Vegas, Nevada. His short fiction has appeared in MetaStellar, Cosmic Horror Monthly, and Diabolical Plots among other published and forthcoming works. You can find links to his works and where else to find him at flow.page/mattbliss. when i suspect that i am rotting i decide i ought to check, nails slipping into sponge that molds to softness ‘tween my ribs, and— slow-- peel back what fetid flesh conceals the compost heaped up just-below old organs, here; emotions older tissues used and damp and torn; my soiled hands dig until i find what writhes, worming within the warm of layers, strata, deadened selves there’s lichen scabs that texturize my time-worn, fear-bleached bone, while fairy rings of feedback loop in endless, nerve-branched loam since nectarous secretions reek of corpses more than flowers, i realize i indeed must say: i am mottled with decay but that will soon enrich the way; as fertilizer feeds the weeds, growth is growth in my small plot and there is beauty in the rot  LB Waltz (@balmroomdance) has been publishing creative works for over 20 years under various pseudonyms. They enjoy taking walks, biblically accurate depictions of angels, and reading about botanical folklore. He claws awake in close, utter darkness, the scream tightening in his throat. He has no idea how he’s gotten here, no thought for whatever he was before, only knows that whatever he was is now trapped in a little narrow box of a space. With a shove and a gasp he flies up, the coffin lid breaking apart in his flight. The man shakes his head, stares about gasping with those panicked breaths that he’s gradually realizing do not draw air. His coffin floats in a pool of oil-black liquid under a dull grey sky; other coffins bump against his, floating alongside, just as dark as the substance that bears them. Many coffins. In fact, with a yawning indefinably huge fear churning within him, he looks about and sees that there are nothing but coffins, coffins and shadow-black ocean stretching beyond even the concept of a horizon. He is dimly aware of something far off in the distance, set an eternity beyond any number of bobbing coffins, a light that is somehow dark, shining weak through the gloom. Framed against this ambiguous light he sees her. A woman, clothed in what might be black or what might be white; her aspect shifts before his unblinking eyes. She’s beautiful in a way that he can’t describe, not beautiful in any way that he desires, but beautiful in the way that a storm cloud or a tumultuous ocean is beautiful. Tousled black hair blows in a breeze he cannot feel, drawn totally horizontal as if some gale blew at her back. Her eyes glitter in his direction and he detects an alien version of what seems to be surprise. Gliding over what could be water, she comes his way, drawing fingers that dangle at the ends of arms that seem far too long for her body along the surface, the ripples gently tousling the coffins about them. “You’re not supposed to be here,” she says, her voice far more casual than he’d expected. “Where?” he says, trailing off, instinctively realizing the question’s useless. She touches his face with a finger, and it does not feel like a finger. It feels like a tendril, like an insectoid proboscis, like some pseudopod made of something that could only fit the basic description of matter. “Between life and death,” she mutters. “This happens sometimes. I do not know where you were destined for, traveler, but when one comes awake as you have, they have a choice. Your path may be set upon eternal glory or eternal suffering; I know not the deeper nature of either. What do you think? How did you live your life?” “I don’t know,” he says. “I don’t remember.” “They usually don’t, but I figure it’s worth asking in case one ever does,” she muses. “Would you like to go back? Back to your life, to what you know as reality?” He wonders, wonders at what that’s even like. But something fundamental in him reaches for it in a desperation he could never put into words. “Please,” he gasps. “Fair enough,” she says, and the black waves wash over him, dragging him down. He looks up through the murk, sees her a moment more as one last lingering pinprick of something not unlike light before the darkness washes over him and he awakes. Clawing awake in close, utter darkness. This time, when he slams his hands against the coffin lid, it does not budge; dribbles of earth rain in between the cracks in the wood. He feels the bursting pain in lungs denied air, feels the sting in his throat as he tries to scream. He claws until his nails rip from his hands, screams that dry scream until he can feel his throat tear, and still he does not die. Distant he hears what sounds like the woman’s otherworldly laughter, and his mind breaks beneath the looming weight of eternity. When he is not writing weird fiction, Dennis Conrad is a high school language arts teacher, giving him the perfect captive audience for his bad amateur stand-up. His works have been published in Third Flatiron's Brain Games: Stories to Astonish anthology and the short story collection Gather Round: The Internet's Scariest Campfire Stories.

You think I’m useless, don’t you? There’s no need to lie; we’re all adults here. You think I’m a piece of junk. I’ll give you that. Look at me. I’m covered in rust and dirt, literally rotting away in your backyard. Oh, woe is me! You should’ve seen me in my prime. I shone so brightly you could’ve used me as a mirror. That’s no hyperbole, mind you. I swear by the memory of my dear master. Yes, he’s dead. Long dead, actually. How did he die, you ask? Well, I’m the one responsible. I… killed him. No, don’t look at me like I’m a monster. I’m far from it. An unfortunate accident. I must admit that his death was my downfall. One fateful night, we stood on a wooden stage downtown. The crowd cheered and clapped, and we bowed before we even began. His secondhand tuxedo looked newer than it actually was. My master waved a gloved hand, and the crowd went dead silent. “Don’t try this at home,” he said with a smile. He lifted me, holding me up in the air like a triumphant warrior, and for a few wonderful moments, I gleamed under the stage lights. Another round of applause exploded. It was perfect. He looked heavenward at the rafters, mumbled his prayers, straightened his spine, and slowly inserted me inside him through his mouth. He didn’t even blink. What a brave man my master was! They didn’t call him Deep Throat for nothing! I passed his teeth and down his esophagus until I reached his stomach. It was like falling through a long, dark hole forever. Acidic air tickled my blade, and I would’ve sneezed if that was possible. Then, unbeknownst to me, a stupid fly perched on my master’s face. I couldn’t see a damn thing in the pitch dark, but my haft told me about it later. How the fly crept toward his nose. Achoo! You can imagine the rest. Yes, there was blood. A lot of it. As its sweet smell filled my nose, I tried in vain to fight off my urge. The MC called for an ambulance, but it was too late. The paramedics threw up their hands. There was nothing they could do. Come again? Do you mean blood? Once you taste it, you won’t forget it. Trust me, you’ll want to come back for more. Hey, why don’t you take me to your garage? Turn off your iPod, won’t you, sweetheart? Oh, easy there. Be careful. I don’t want you to get distracted. Remember, I’m designed to cut. Watch your step. I don’t want you to slip and fall, okay? Here we go. Even the noise of the garage door opening sounds melodious. Grab that piece of sandpaper. Here we go. Come to Daddy. Yes, that feels so good. You scratch my back, and I scratch yours, right? You won’t regret it. Decades in dirt. Imagine that. Who deserves that? Not me. No wonder I’m so thirsty.  Toshiya Kamei is an Asian writer who takes inspiration from fairy tales, folklore, and mythology. Their short stories have appeared in Cosmic Horror Monthly, Galaxy’s Edge, and elsewhere. Their piece, “Hungry Moon,” won Apex Magazine’s October 2022 Microfiction Contest. https://toshiyakamei.wordpress.com/ I am the watcher at the end of the world. Or- At least, that’s what I like to tell myself. It would be boring otherwise. This whole situation would seem anticlimactic and agonizing without those little reassurances. I need little reassurances as the landscape around me plunges into its season of darkness. March brings with it blistery winds and never-ending midnight, as the wintery rolling hills shift from a blinding white to a crystalline blue. Peppered with glistening specks like the remnants of starlight tossed to the wayside by the hand of a deity who gave up on their creation. A midnight that brings on shadows, shadows accompanied by the sharp gnashing of teeth in the form of bitter winds. The spirits of the planet seem to cry out in rebellion, in anger against the thunderous boot prints humanity stamped upon its once proud face. The night is long and cold. Antarctica is cold. This outpost is cold and I am a fool for opting to stay one more season. One more season turned into two. Then three. The last I heard from the mainland, from my employers, was that something catastrophic happened. It started in North America and spread outward, bouncing across the landscapes like a doe over fresh fallen snow. I heard the sky tear. Something shifted the course of humanity, of Earth, and radio silence quickly followed. The receiver doesn’t buzz anymore. So I sit here alone, gazing at the wide open expanse of tundras and tidal waves of snow with bleary eyes and a growl in my stomach. Waiting for a call, a plane, another human face in the blanket of endless white. A confirmation that the end has arrived so I can stop drowning in my anxieties and what-ifs. Pondering the fate of the planet out beyond the winter wastelands. Out beyond the technology-laden halls of this damned building I now call home. It’s lonely at the end of the world. I’m bored of soup, of puncturing the cans open with my knife and wishing it was warmer than it is. It can be scalding and still not be warm enough. I’m tired of listening to the walls of machinery scream at me that something is wrong. My heavy coat feels all the heavier over my shoulders as it becomes a necessity. Another layer of skin, toned army green. My notebooks—meant for research—have filled themselves with mindless nonsense as I jot down my thoughts. The lines of binary have turned to swirling cursive. Zeroes and ones turn to poetry and prose as I try to process the eternal damnation that sits outside of my window. I wait in my tower, like a forlorn Rapunzel, praying for someone to breach my walls. Lost in the metal spire, in my outpost, with a sad beeping radar to keep me company with its uneven and rhythmless melody. All I can do is wait and watch. Wait and watch. Wait and watch at the end of the world. And so I watch. Watch the planet melt and the stars burn out in real-time, amplified by the isolation at the end of the world as the horizon line tears asunder. And I think to myself, “Was this worth it?” I don’t know. It’s hard to tell, hard to justify, hard to grasp. Was the research worth it? Was the stint in this cold box worth it? Being away from my family? My friends? My lover? Was sitting in the silence, in the chill, worth all of this? Wondering if I’m the last human alive, stuck in that split where the snow meets the stars. Where the glisten on the ground is indiscernible from the twinkle in the sky. Where the whole of the world becomes a snow globe of stars, shaken until they come loose and fall in spirals like a meteor shower, and I feel my body twist alongside their trails, tumbling without gravity. I am without gravity here. Was it worth it? Yes. Yes. A thousand times yes! In this isolation, the quiet and loneliness and wondering and waiting and hoping and watching at the end of the world meant I could gaze upon the colors with my own eyes. The aurora wafts with twisted lines, blown in like a gale on the surface of the ocean, calling lost souls toward where I am stranded. Stranded in my lightless lighthouse that dreams to beckon to someone with no avail. For a brief moment, it shifts the unnerving blue, the unyielding darkness, to something magical. Otherworldly, like a massive hand tearing through the fabric of reality to peer down at the chaos with wonder and a cocked eyebrow filled with question. I see the universe shatter. I see the eyes of something greater than myself peer down with question. The creators did not forsake us. No. Not yet. They still have judgement to pass. I stand in the snow, starving and frozen, on what may be the last night of my life. I stand still, hood caked in crystals of ice and cheeks so painfully brushed by the wind, and I gaze at those glowing eyes, white-hot like a sun. I see its hand stretch out to crush the crust below me. I feel those damning winds rip the tears from my eyes, clog my pores with ice and freeze my blood as quick as a bolt of lightning. Unable to do more than drop to my knees and watch the end of the world ripple. Watch this deity collapse the universe with quick and chaotic brushstrokes, lighting the darkness for the briefest of moments and I think to myself, yes, this was worth it. Watching the world unravel like a worn-down cardigan was worth it. Watching the universe explode in magnificent shades was worth it. Watching the end of it all at the end of it all was, most assuredly, worth it.  A.L. Davidson (she/they) is a queer and disabled writer who specializes in massive space operas and tiny disturbances. She writes stories about ghosts, grief, isolation, space exploration, eco-horror, queerness, and the human condition. They live with their cat Jukebox in Kansas City. Their debut novella, When The Rain Begins To Burn, was funded via Kickstarter and they hope to have many more books follow suit in the near future. Her web novels, The Wayward Souls of Avalon and Lonely Planet Hotel are available on Patreon and Tapas. Disturbances by Alycia Patreon - Alycia Davidson Author Twitter - @MayBMockingbird Insta/TikTok/Threads/Blue Sky - @MaybeMockingbird |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed