|

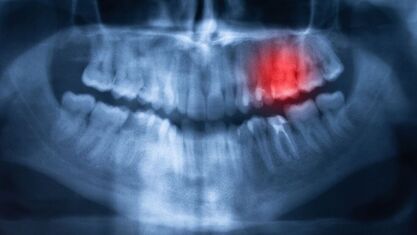

The twins are up past their bedtime, the sounds of a bloody creature feature turned down low on the bubble-fronted basement television, so that their parents upstairs won’t hear them. They’re giddy with the rush of the forbidden, of trespassing, transgressing. It’s a glee that’s cut short just when it’s getting good, when the monster is about to be revealed, because the television cuts to black. But it’s timed wrong, in the middle of a scene, in the middle of a line of dialogue, so they keep their eyes on the screen, and see only a grainy close-up of a man sitting in front of a black and white chevron background. It is not an ad. Not any they’ve ever seen. And it’s not a man. Not any they’ve ever seen. His smile, his whole face is unmoving. Sunglasses shield his eyes, his hair a platinum plastic pompadour. “They… are coming… to get me,” he says from behind the mask. The boys know that they shouldn't see this, even more so that they shouldn’t have been watching the monster movie. Not in the sense that it came to them by mistake, but that they shouldn't. See. This. That it's against some rule of the world they don't understand yet. They look at one another, the silent question, should we? drifting between them. When neither of them voices an objection, they confirm their decision. The masked man disappears, and they keep watching the unspooling of seemingly-unrelated images. They cannot look away (waves crashing against an unfamiliar, broken shore), suddenly imagining some invisible force holds them steady. Peels their eyelids open. Points their faces at the screen. When they take into account what they see on the television (a close-up of a woman with a ball gag in her mouth, looking wide-eyed into the camera), this seems less farfetched. And when it's all over, and the television has returned to its normal late-night rerun of whatever monster movie they were watching that no longer seems important, they can't describe what they've seen. Not entirely. Nor can they properly describe how it made them feel. Only in snippets can they do either. It's like the images (a brown paper bag over the head of a barefoot lady in a floral dress, hands held out at her sides for balance despite her standing in the grass) are part of a dream (she steps forward carefully, tentatively, unaware of the coiled snake by her feet). Not theirs, but someone else's they accidentally stumbled into. The feelings, however, the reactions, are entirely their own. The boys look at one another. Neither one of them speaks, but they each know the other is sweating (just like the blindfolded man, sweating, running, the look of terror on his face, the camera moving ahead of him, looking over his shoulder, spying the dark, loping, out-of-focus shapes he’s fleeing). Under their armpits. On their foreheads. Rivulets running down their backs (a shot from behind of a toned woman in the dark, her muscular back laced with fresh, bloody wounds, something moving in the darkness ahead of her, something she looks ready to fight again). The boys do not yet have the vocabulary to explain what they’ve seen, how it’s made them feel other than wrong (a woman in a pencil skirt bending herself over a pommel horse, looking back over her shoulder at the camera as she spreads her legs). And yet there is no proof that any of this ever happened. Nothing except their memories (the woman in the dress holds the snake carefully, coiled around her bare forearm, extended, holding it out like it’s going to fly away and she’s going to guide it), their feelings.  T.T. Madden (they/them) has been writing horror, scifi, and fantasy ever since they tried climbing (and were unfairly pulled from) their mother's bookshelves to reach her Stephen King novels. So to get their fix they visited the library, and their local Blockbuster (which didn't check ID). They have two books releasing in 2024; The Cosmic Color, a transfem mech/kaiju novella with Neon Hemlock, and The Familialists, a queer social horror with Off Limits Press. They can currently be found in the deepest, darkest part of the woods, finishing a folk horror novella. But for a more normal method of contact, try @ttmaddenwrites on Twitter, Instagram, Bluesky, and TikTok. Every woman in my family has known she was going to die when one of her teeth fell out. It’s our curse. I don’t mean the baby teeth, that would be truly fucked up and I wouldn’t even be here right now if that were the case. At some point in every Murray woman’s life, one of her molars will fall out to signal that her time is near. My mother, Winnie, knew she was going to die when she was in the middle of the grocery store trying to decide between a roast chicken and ground beef when a sudden crack resonated through her head. She felt the loose piece of bone swimming through her mouth towards her lips and held her hand out to spit out and bear witness to Death’s calling card. My dad tells me she just shakily placed the tooth in her purse and picked up the roast chicken. After all, my family still has to eat, she said. She died one week later. I was ten. The length of time is never consistent, but it’s always within a month. My aunt Tess died in the bus terminal still clutching onto the foreboding ivory that had fallen just moments ago. My grandmother held out for almost two weeks before whatever malevolent force took her away. Some of my family tried to fight it. My cousin, Emma, avoided all solid foods so as not to disturb any of her teeth. She died at Thanksgiving dinner with only pureed carrots and peas on her plate. My great-aunt Dot thought that if she super glued her tooth back into her mouth then that would trick the God coming to take her away. She lived the longest. Twenty days after she glued her tooth back in she passed away during a routine teeth cleaning. Her husband, Greg, insists that the hygienist knocked the tooth out of place and that she should be sued. Of course, those outside the family don’t understand our plights and Greg lost the lawsuit. And my poor sister, Judy. She was only twelve. She came into my room one night, tears sliding down her face, but she wouldn’t tell me what was wrong. She just asked if she could sleep in my room that night. When I woke up the next morning, my arms were wrapped around a cold body, and my sister had been taken at some point in the night. I found the tooth under her pillow a few days later. That was the last straw for me. That some stupid force in this universe would choose my twelve-year-old sister rather than someone else to die. She was still a kid. From that day on, my soul rotted to the core, and I turned bitter. Dad understood, but he wanted me to move on. Can you believe that? Move on when there’s a fucking curse on our family and every fucking woman born with the Murray name dies once one of their teeth falls out! How am I supposed to move on? How is anyone supposed to move on? Dad most of all. He’s lost his wife, his youngest daughter, and he thinks he’s going to lose me at some point. Well, he’s wrong. I’m not going to let some laughable curse take me away from this world before I say so. And, yes, I hate the world that I live in. Everyone I’ve loved has been taken away from me too soon and without reason. You’d think I’d be happy to die and finally reunite with all of my lost family members. Feel the warm embrace of my mother that I haven’t felt in fifteen years; crush my sister into a bear hug and smell the strawberry scent of her hair; laugh at my aunt Tess’ dirty jokes and watch the food fly out of my great-aunt Dot’s mouth as she cries hysterically. I would be reunited with all the wonderful, disgusting things that have left a gaping hole in my heart once I was left with a gaping hole in my mouth. And as much as I want, need to see them, I can’t do that before my time—my true time. I stare in the mirror now and smile. I smile bigger and bigger until I’m satisfied. My cheeks hurt from the magnitude of my grin, and tears leak from my eyes. I did it. I did it. I got every last one. My mouth is now just some yawning black hole. The pearly whites that were there my whole life, including the one to determine my destiny, are now gone. Pulled out; the roots ripped away like the maternal roots of my family tree. Pulling them out hurt, obviously. I rubbed an Ibuprofen gel capsule on my gums to numb them, but that didn’t stop me from feeling the twisting and yanking of twenty-eight teeth. Not to mention those that didn’t come out easily, breaking into shards and causing me to go back in more than once with my pliers. My fleshy pink gums glitter back at me as I continue to smile at myself, the tears of relief flowing freely down my face. I can feel my mouth humming from the exposed nerve endings, and I know realistically I’ll have to go to a dentist to fix that, but I let myself bask in my triumph. No more seeds of doubt will bloom within my mind, and the seed of my death will no longer take root nor flourish nor finally wither away and fall like the leaves in autumn. Whatever miserly deity rules over my family will not reap what they sowed in this Murray woman.  Katie Cossette (she/her) is a Montreal writer pursuing her BA in Honours English Literature. Her work has been featured in DarkWinter Lit, Ghost City Review, Alien Buddha, Wireworm, and elsewhere. Katie is currently the co-founder/co-EIC of Crab Apple Literary and you can find her on Instagram (nerd.i.am) and Twitter (cossette_katie). |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed