|

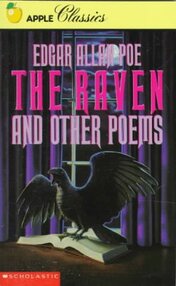

I can’t remember the first time I went to a bookstore. I mean a store whose central product is books. Growing up in rural parts of Utah, I had the Scholastic Book order forms, like so many others of my generation. I don’t think Scholastic gets the credit they deserve for being a publisher of gateway horror. My first copy of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark came from them, as did the gloriously skeletal—but ultimately disappointing--The Train by Diane Hoh. My memory wants me to believe Scholastic published Christopher Pike, too, but I never bought any of those. Two other things found in the book order form helped make me the horror writer I am today. I still have the first copy of Edgar Allan Poe works I ever bought. The Raven and Other Poems was an Apple Classic from Scholastic and, as you can imagine, the cover was gloriously purple. I must have known something about Poe before buying it, but I don’t remember. “The Raven” hypnotized me and “Annabelle Lee” made me cry, although I didn’t fully understand it at the time. I had not read much poetry outside of Shel Silverstein—a good precursor to reading Poe, in my opinion—and so it took some getting used to the format. The slim volume was only poetry and so I would soon search out the short stories and began to notice how often Poe showed up in other media. I remember one episode of the sitcom Cheers in which Carla invoked the spirit of “The Tell-tale Heart” to freak out someone else at the bar. Later there would be The Simpsons epic version of “The Raven” pitting Homer against Bart the raven. Around this time, ages nine to 13, I truly began to embrace horror. I had been a casual fan and a sufferer of nightmares. But my birthday is on Halloween, and I soon sickened of other people scaring me. It was my turn. Re-enter the Scholastic book order form. During my sixth-grade year, Scholastic sponsored a contest to complete an unfinished R.L. Stine story. Later, as Stephen King took over my reading life, I learned that King had done the same thing with a men’s magazine in the 1970s. “Finish this story,” beckoned the flimsy catalogue. So I did. I took Stine’s story of basement experiments and paternal secrets and created a Moreau-esque bird monster. I did not, however, win. I could consider this my first rejection but more importantly, it was the first real story I finished. The Goosebumps book that Stine’s start later became featured sentient and monstrous plants, not a birdman, so at least he didn’t steal my idea. Someone won that contest and I hope they stayed the course and became a writer. What I got out of that story, besides the important act of finishing something, was a nomination by my teacher and acceptance to the Utah State University young writers conference. My mom and I got to spend the day on the college campus. Somebody gave a speech, we were given lunch, and I got a medal. We also got to hear other participants read their stories and essays. We heard quite a bit of monotone reading, but I wanted to scare people. That was my first public reading. Gasps at the scary parts and a round of applause and that was it for me. Even though I didn’t immediately devote my life to writing, I always craved the applause… and the screams. I’ve done theater and worked in haunted houses. Those are all collaborative experiences. I might be the focus in the moment, but there’s a mask or a character between me and the audience. There’s the set and maybe music. During a reading, it’s only me and the words I put down on paper. A reading is a performance. I’ve read about Poe’s public readings and attended a large outdoor reading by Stine. I know they both understand. Without them, and the access to their work via the Scholastic book orders, you wouldn’t be reading this now.  T.J. Tranchell was born on Halloween and grew up in Utah. He has published the novella Cry Down Dark and the collections Asleep in the Nightmare Room and The Private Lives of Nightmares with Blysster Press and Tell No Man, a novella with Last Days Books. He has been a grocery store janitor, a college English and journalism instructor, an essential oils warehouse worker, a reporter, and a fast food grunt. He holds a Master's degree in Literature from Central Washington University and attended the Borderlands Press Writers Boot Camp in 2017. He currently lives in Washington State with his wife and son. Follow him at www.tjtranchell.net. Who saw the Farmer’s Wife fall facedown on her bedroom floor, crushing her Sunday hat? Who watched her shake and bubble up like skillet bacon? Who then saw Farmer McKidd himself approach his fallen wife, like she was some ornery goat, the way she kicked out at him with her hind legs and her gurgling wheeze, which sounded so very barnyard. Farmer McKidd got kicked several times by his wife that day, until he finally retreated into the kitchen to figure out how to fix his wife. He opened the fridge and didn’t find any answers in there. Just a little leftover ham. He ate some to help his thinking. He stood in that kitchen, chewing that ham and listened to his wife kick over her lamp and then trample her prayer stool. He tried not to listen to all her foul language, but it was hard. She was so articulate. He stared out the kitchen window for strength, just in time to see his newborn calf fall dead in the field. The heat was getting everyone. Farmer McKidd rushed out, leaving his wife to curse God and cook up to a fever of one hundred and eight. Who saw beyond the farmer’s field, in the forest, a herd of deer standing in a perfect circle, communicating their thoughts telepathically? The deer, though shy at first, were finally able to express to one another their true horror of being caught in the glare of headlights, and the keen yearning they had for their now-dead mothers. Then they wondered about what it was about them that made people shoot them. Their ability to talk to each other this way was a gift, but they weren’t used to it, and it tired them out and then they all drifted apart out of telepathic range. Could anyone have seen further in the forest, they would have seen a man in a suit made of mylar and polymers, now burnt and frayed. Who witnessed the appearance of this man on the forest floor, a man changed by centuries of travel performed in an Earth’s instant? A man lying there, rippling with stories of the cosmos; those stories told by viruses and bacteria that colonized distant worlds and then destroyed them? Who could see that the man was neither dead nor alive, but was warm with the blood of the thousand worlds he had visited? A tick. A tick saw all this happen. The tick that made its way to the spaceman and pulled out the blood. Then moved onto the deer. Then finally to the Farmer’s Wife where it now sat, bulging with blood, in the nest of her hairline. The Farmer’s Wife was getting the benefit of telepathy too, and suddenly knew all her husband’s thoughts that he’d never dared speak aloud. But she was also tasting the fall of Europa. First comes the kicking and the squealing. Then her flesh will peel off and wander away and attach itself to the nearest rock or tree. The tick would climb off the farmer’s wife before that happened. It would find a nice warm cow or the neck of a sheep dog, and would pass along the messages from those strangers in the cosmos.  Mary Crosbie howls from Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Gross and Unlikeable, Blood Bath LitZine and Space Squid. Follow her on Twitter or her website: Www.marycrosbie.com To start with, the TV people were excited about Mars being the closest that it had ever been to earth. Now, mom says I don’t have to go to school so long as I don’t turn on the TV or look out the window. She makes me play games like boarding up the doors. She says it’s fun, but it is not. Neither are the screams outside. I miss the sun’s heat on my face and the cooling rain, but I made a promise—I will not look outside. Even when I recognise neighbors' voices begging for help. Sometimes there are gunshots, or the screaming goes on throughout the night. Mom says they are dreams—all good boys have them, but now I’m starting to think the closeness of Mars is driving mom crazy since the food is running out. I said I didn’t mind going to the store. However, Mom laughed and told me there was more than enough food. The cooked meat tasted like chicken, but when I tried to find my cat, Argo, I couldn’t. Mom says he must have run away, but he’d never do that. Not after I found his collar in the trash can. Now all mom does is cry when she thinks I’m not looking. I wish I knew what to do. I wish that I could help her or look out the window and see Mars’ beauty. Before the TV went off, they said it would be a once-in-a-lifetime thing. That the populace devoured too many trash movies—now was the time to look up to the heavens. But mom won’t let me go outside. She says only naughty children look at Mars. Things are getting so bad that I’m ready to return to school. Staying indoors 24/7 is making me crazy. But when I tell her that, mom just cries more. To pass the time, I pick at forgotten books; some are history, some describe this war God Mars who gave his name to the red planet. I have yet to find ONE nice story about his terrible fury. Everything he threw his crimson light at he destroyed, and I wonder what could be so beautiful about the little red planet now it’s so close to earth. Even though I promised mom not to peek, sometimes I wonder about that a lot.  Matthew Wilson has been published in Star*Line, Night to Dawn magazine, Zimbell House publishing and many more. He is currently editing his first novel and can be found on Twitter. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed